Freezing Your Future Fertility

Advances in egg freezing offer women new alternatives, but cryopreservation isn’t their only option

Fertility doesn’t matter until you need it. Many women envision starting a family one day, but the unfortunate reality is that one in eight females will have trouble conceiving or sustaining a pregnancy.

Several medical conditions and risk factors make getting pregnant difficult:

- polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

- endometriosis

- being overweight or underweight

- fallopian tube damage

- uterine or cervical abnormalities

- tobacco and alcohol use

- too much or not enough exercise

- advanced age

Of these conditions and risk factors, age is possibly the most difficult to address, because it cannot be reversed.

The good news is that in just the last decade or so, biotechnology has delivered an increasingly attractive alternative for women approaching the end of their childbearing years.

The alternative is egg freezing – or, in medical terms, oocyte preservation – and it’s time for young women to know more about it. It’s also time for them to understand fully the risks of postponing motherhood before egg freezing becomes their last viable alternative.

Women shift priorities

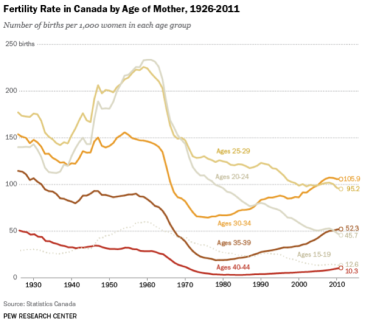

Delaying motherhood is on the rise across North America. For more than three decades, birthrates among Canadian women older than age 30 have been on the rise, while childbearing has significantly fallen for Canadian women younger than 30.

A 2013 report by Statistics Canada shows 52.3 babies were born per 1,000 women ages 35 to 39, higher than the 45.7 births per 1,000 for women ages 20 to 24. The report also shows that birth rates for women in their early 40s are now nearly as high as the teenage population.

The consistent decline in births for women under 30 can be explained, in part, by improved fertility education and greater access to contraception.

But why are Canadian women waiting to have children?

The dominance of women in the workplace and a redefining of familial roles are likely contributing to women having their first child later on.

At OriginElle, our patients often say they are hesitant to start a family due to tight finances, or they have not yet found the right partner, or are seeking advanced degrees, or have put their career ahead of other life aims.

The limits of female physiology

Unfortunately, human biology limits a woman’s ability to continue producing viable eggs.

A girl is born with 1 million to 2 million eggs in her ovaries, and she cannot produce more in her lifetime. By the time she hits menarche (puberty), an average girl will have roughly 300,000 eggs, losing about 1,000 every month.

A woman’s ability to conceive subsequently declines significantly after age 35; by the time she turns 40, her pregnancy potential is cut in half. This reduction in eggs is referred to as low or diminished ovarian reserve.

Additionally, children born to older women are at a greater risk of birth defects. New research suggests that chromosomal errors resulting in birth defects have less to do with the egg quality and more to do with the mother’s age and the resulting physiological changes that degrade the quality of eggs in the ovary.

While the fate of women waiting past age 35 to get pregnant sounds dismal, women who plan ahead can nevertheless expect to give birth to healthy children well into their 40s with the assistance of egg freezing.

The history of egg freezing

Egg freezing has been an option since the first birth from a cryopreserved egg reported in 1986. At that time, cryopreservation of oocytes was fairly unsuccessful and labeled as experimental. Pregnancy success rates from frozen eggs were as low as five percent.

This forced women (typically cancer patients) to preserve their fertility by freezing their embryos (fertilized eggs), which proved to be much more successful than egg freezing.

Thanks to advances in technology, however, a new method of cryopreservation called vitrification has greatly increased the ability of oocytes to survive freezing and thawing.

Vitrification allows fertility specialists to speed up the freezing of eggs to guarantee higher rates for the successful thaw. Subsequently, frozen egg survival rates have surpassed 91 percent.

Vitrification also generally improves embryo creation and growth of the embryo to the blastocyst stage, the healthiest stage of embryonic development before implantation into the uterus.

With the evolution of vitrification, a 2012 ruling by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine lifted the “experimental” label from the practice of egg freezing. This opened the doors for women to freeze their eggs for social reasons (as opposed to medical needs), often referred to as elective egg banking.

The role of egg freezing in a broader strategy

Just a few years ago, the odds of success of IVF with frozen eggs was roughly half of its current rate of 60 percent or better. While scientists are unsure how many years an egg will remain viable in the deep freeze, we expect that eggs properly are frozen and cared for could last generations.

Although pregnancy past the early to mid-40s is generally not a great idea except in extraordinary conditions, vitrification has attracted a brand new pathway to parenting. So vivid is its potential that one day girls may routinely conserve their fertility using their personal egg lender and might also can it unto their brothers.

However, in the meantime, we as a society have to encourage different options. Primarily, we can guarantee that young girls are far better educated about the dangers of postponing motherhood — decreasing fertility, improved likelihood of miscarriage, and chromosome abnormalities.

Secondly, society should find ways to support women giving birth at younger ages without affecting their careers.

Lastly, for those young women who still choose to postpone parenting, they should be fully aware of the alternative of egg freezing.

This trio of initiatives forms a comprehensive strategy whose time has come.